The seventeenth century was one of the most turbulent times in English history. One of the defining and unusual moments in this era was when England was known as a unique time without a king, known as the English Interregnum.

From the execution of King Charles I in 1649 and the restoration of Charles II in 1660, England engaged in a political experiment. This brief period significantly reshaped government, religion, and society, leaving behind valuable lessons for the future of monarchy and democracy in Britain.

Understanding the English Interregnum

The word “interregnum” can be defined as “between reigns.” The English Interregnum refers to the time frame once King Charles I was executed when there was no king until the monarchy was restored. For the first time in England’s history, there was no king or queen, and England was experimenting with republican forms of government.

The nation was first governed by the Commonwealth of England, then by Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate, and finally by Richard Cromwell, before collapsing into political chaos, which allowed the monarchy to return. This time was not only about the figure of power. It was also a test of whether England could exist without a monarch.

The interregnum in the British Isles began with the execution of Charles I in January 1649 (and from September 1651 in Scotland) and ended in May 1660 when his son Charles II was restored to the thrones of the three realms, although he had already been acclaimed king in Scotland since 1649. During this time the monarchical system of government was replaced with the Commonwealth of England.

The precise start and end of the interregnum, as well as the social and political events that occurred during the interregnum, varied in the three kingdoms and the English dominions.

The causes of the English Interregnum

In order to understand what caused the Interregnum to occur, one must examine the events of the English Civil Wars.

Conflict with Charles I

During the reign of King Charles I, the king consistently struggled and failed to cooperate with Parliament over money, religion, and royal prerogative. Charles believed in the “divine right of kings,” while Parliament believed that there needed to be limits on his prerogative.

Civil War and Defeat of the Monarch

From 1642 to 1649, England became torn apart in civil wars between the Royalists, who backed the king, and the Parliamentarians, who became known as Roundheads. The army supporting the Parliamentarian cause, known as the New Model Army, emerged victorious in their defeat of the king’s supporters under the profile of Oliver Cromwell.

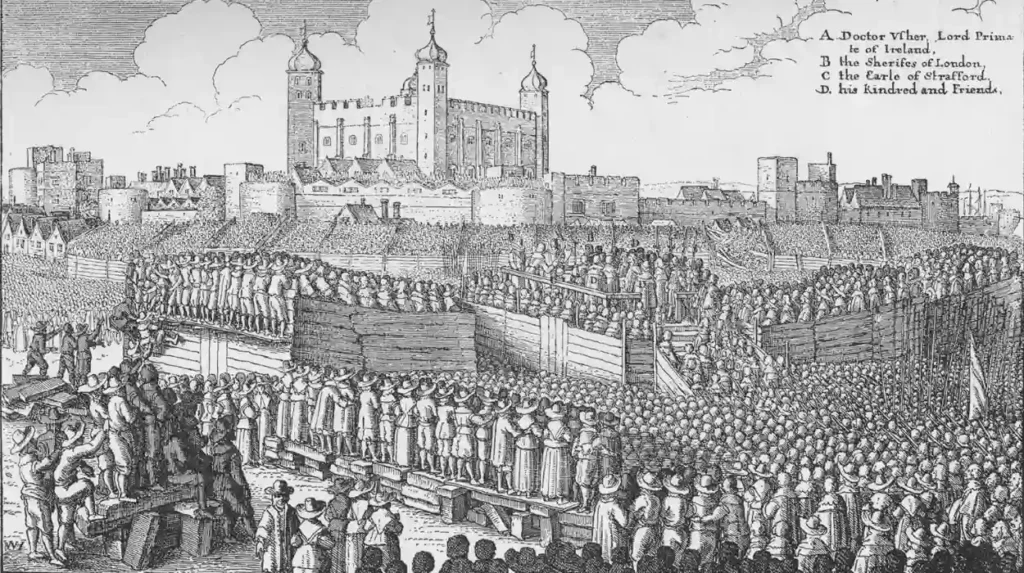

The Execution of the King

In January of 1649, Charles I was tried and found guilty of treason and executed. His execution shocked Europe, as it was the first time an English monarch was formally tried by his own government. The monarchy was abolished, and the Interregnum began.

Stages of the Interregnum in England

The Interregnum can be divided into three identifiable stages:

1. The Commonwealth of England (1649–1653)

With the execution of Charles I, England was considered to be a republic (Commonwealth). The Acting Convention specified parliament as the ultimate authority. Political divisions became apparent soon after the revolution, with radical groups (such as the Levellers), Presbyterians, and the army.

After a brief period of governance, the Rump Parliament found itself unpopular, regarded as corrupt and incompetent. Oliver Cromwell, with the army, dissolved Parliament in 1653.

2. The Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell (1653–1658)

Oliver Cromwell, a capable military leader, was now Lord Protector. He established the Protectorate, a new regime that contained republican features yet exercised near-monarchical powers. Cromwell’s Puritan heritage would ensure the maintenance of severe manners of Puritan morals.

Internationally, England became established in many themes and strengthened their presence and became involved with winning trade wars against the Dutch and waged campaigns in England and Scotland.

He provided leadership and stability for England in his realm. Cromwell could never accept the relinquished crown of England, as he considered the act a compromise of core revolutionary ideals. The protectorate was potentially better than other forms of governance, albeit Cromwell led more like a dictator than a democratically elected leader.

3. Richard Cromwell and Collapse (1658–1660)

After the death of Oliver Cromwell, in 1658, Richard Cromwell was designated leader of the Protectorate but was neither a gifted military leader nor an articulate speaker. Richard, his father, was poorly equipped because neither had military experience nor political power.

The army did not trust him, and Parliament lost confidence as it was split. Within a year, he was forced to resign. Disorder allowed for monarchy to be restored under Charles II in 1660.

Life during the Interregnum

After the Parliamentarian victory in the English Civil War, the Puritan views of the majority of Parliament and its supporters began to be imposed on the rest of the country. The Puritans advocated an austere lifestyle and restricted what they saw as the excesses of the previous regime.

Most prominently, holidays such as Christmas and Easter were suppressed. Pastimes such as the theater and gambling were also banned. However, some forms of art that were thought to be “virtuous,” such as opera, were encouraged. These changes are often credited to Cromwell, though they were introduced by the Commonwealth Parliament.

Why Did the Interregnum Fail?

The Interregnum failed for many reasons:

- Disunity: The army, Parliament, and various religious factions constantly clashed.

- Dictatorial Tendencies: Cromwell effectively ruled; it felt like a monarchy dressed in different clothing.

- Harsh Reforms: Cromwell’s strict Puritan laws began to turn ordinary people away.

- Poor Leadership After Cromwell: Richard Cromwell was unable to hold it all together.

Ultimately a lot of English people preferred the certainty of monarchy rather than the uncertainty of republicanism.

The End of the Interregnum: The Restoration of 1660

In 1660, General George Monck marched the army into London and demanded for the monarchy to be restored. Charles II, the executed king’s son, was invited back to the throne. The Restoration in 1660 marked the end of the English Interregnum. The monarchy was restored, but it would not be unchecked. Parliament’s role in governance had been significantly strengthened.