Constitutionally, could Parliament abolish the UK Supreme Court? It sounds sensational, but it’s a traditional challenge to the UK’s uncodified constitution. The Supreme Court has acted as the final court of appeal for civil matters in the UK and for criminal matters since 2009 in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, as well as the constitutional referee for devolution disputes. However, there is no single entrenched constitution in the United Kingdom, which means – in principle at least—that what can be created by Parliament can be un-created by Parliament.

What is the UK Supreme Court?

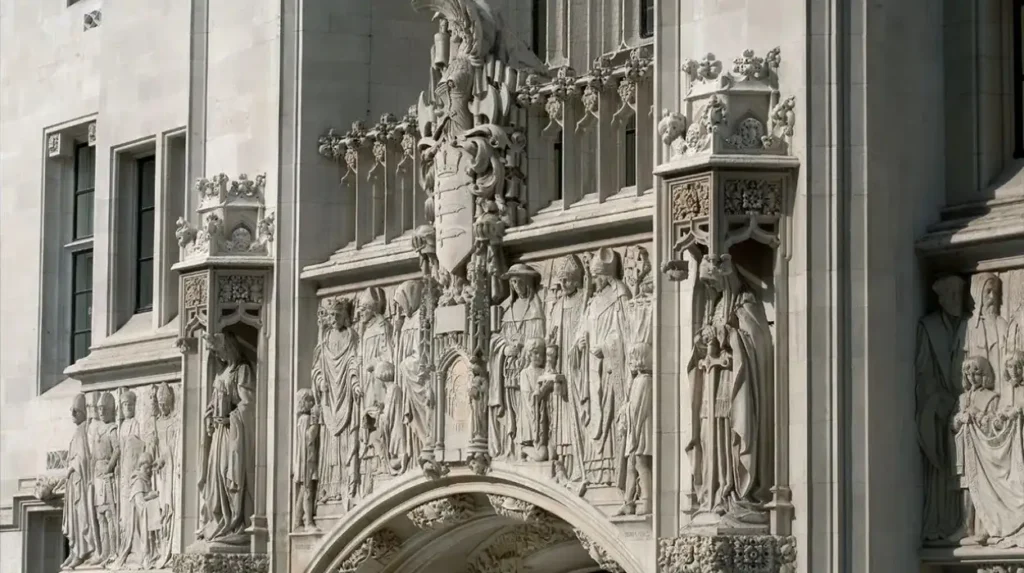

The UK Supreme Court was established by Part 3 of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 (CRA 2005) and started work in October 2009. The UK Supreme Court replaced the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords (the “Law Lords”). In order to clearly delineate the UK’s final court from Parliament, it was important for the UK Supreme Court to be separate from Parliament. In brief, the Supreme Court is a statute-based court, not a creature of common law or royal prerogative, and its existence exists only under the authority of an act of Parliament.

Parliamentary sovereignty: the core reason dissolution is legally possible

Before we consider particulars, we must first clarify orthodox doctrine. Parliament is sovereign; it can make or unmake any law. The Supreme Court exists by statute. Void the statute, and you can amend or repeal it, including provisions of the CRA that created the court and its jurisdiction. There is nothing entrenched to stop this. From a black-letter law perspective, dissolution is possible if you are prepared to do so by primary legislation. What follows sets out why “possible” does not mean “easy” and why, given the politics and broader constitutional context, it remains challenging. (For background on the statutory basis and purpose of the Court, see [the CRA 2005 and Parliament’s own history pages].

The minimum legal mechanics: what would have to change?

To abolish the Supreme Court would require the repeal or significant amendment of Part 3 of the CRA 2005 (the provisions that say, “There is to be a Supreme Court of the United Kingdom”) and the related provisions on judges, appointments, funding, and Lords proceedings. That’s only the starting point. There are a number of other acts that route specialist questions to the Supreme Court, especially the devolution statutes for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. All devolution statutes give the Supreme Court fixed functions, both policing the borders of devolved competence and concerning “devolution issues.” Re-routing (or rewiring) these references would be unavoidable if the court were dissolved.

Devolution makes dissolution exponentially harder

All the pieces of legislation that initiate devolution—Scotland Act 1998 (see, e.g., Schedule 6); Government of Wales Act 2006; and Northern Ireland Act 1998—provide pathways for ‘devolution issues’ to reach the Supreme Court (whether law officers are referenced or discussions on whether devolved legislation has acted within competence).

The statutes contain interlinkages with the court and procedures that presume the continued existence of the Supreme Court. Any bill for abolition would need to do all of this work of reworking the pathways and putting in place an alternative ‘final arbiter’ (be it a reconstituted ‘final court’ within the senior courts or some other body). Without this mapping of the statutes’ references to the High Court, the devolution system would simply not be able to run.

The Sewel Convention: not a veto but a considerable hurdle

There is a strong constitutional expectation that Westminster will seek the consent of devolved legislatures when it legislates for devolved subject matters or alters devolved institutions (the “Sewel Convention”). The text of the convention was put in statute in the Scotland Act 2016. The Supreme Court held in Miller (2017) that it remained non-justiciable: it is a matter of political politics, not a legal constraint. In other words, if these countries were not legally entitled to prevent a Westminster bill for the dissolution of the Supreme Court from going forward, Holyrood, the Senedd, or Stormont would suffer political damage should they withhold consent. Any such abolition is almost certainly going to cause consent disputes across the devolved nations.

Independence of Justice: Westminster Duty Exemption

The CRA 2005 also enshrines a statutory duty on ministers, inclusive of the Lord Chancellor, to uphold judicial independence. Even if Parliament allows the recreation or abolishment of the Supreme Court, it must institute it in such a manner that institutional independence, security of employment, and effective access to justice are preserved. A design that appears to fold the final appellate function back into the legislature or places it under executive influence would collide with that duty and could invite domestic and international criticism.

Where Would the Cases Go? Three Main Models

1) Reinstall the Law Lords in the House of Lords. This is the primary historic model that the Supreme Court is supposed to have replaced. Reversing it would create a blurred line between law-making and law-interpreting, which is exactly what the CRA 2005 was attempting to remedy. While legally possible, this would be difficult to reconcile with the contemporary understanding of independence and CRA policy logic.

2) Create a “Final Court of Appeal” as a new court that is part of the senior courts. This approach would simply involve rebranding and relocating this function to another tier of the Senior Courts of England and Wales, each with similar routes for Scotland and Northern Ireland. Overall, this option runs into the problem that most civil cases and all devolution references are UK-wide; thus, it would need a coherent, properly constructed, genuinely UK-wide court or a cohesive set of final courts with a method to consistently resolve UK constitutional questions. The drafting problem (and inter-jurisdictional diplomacy) would be huge.

3) Transfer some constitutional work to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC). The JCPC already does some devolution and overseas appeals. In theory, Statute could expand its UK role. However, to use a body directly linked to appeals from overseas would feel like regressing, not modernizing. Regardless, it would still require reforming the devolution statutes so that appointments could be independent and transparent.

The devolution caseload shows why a replacement must be credible

In practice, the Supreme Court does not solely deal with appeals that can be called “ordinary.” It regularly hears important devolution references from various jurisdictions – precisely the type of dispute that can most benefit from the involvement of a neutral, respected tribunal operating fairly and reasonably across the UK. The recent listings and judgments indicate this jurisdiction is alive and involves concerns of legislative competence and intergovernmental relations. The new body would require clear statutory authority and public legitimacy to make high-stakes constitutional judgments of this kind.

Would the Lords or Commons gain authority or power by eliminating the court?

Not directly. Courts do not “veto” Parliament; they interpret and apply statutes and the common law. The Supreme Court’s most visible constitutional function is to give authoritative answers on questions of law that arise when statutes interact and especially statutes that arise from the devolution settlement and verify that the executive is acting in accordance with law. Eliminating the Supreme Court does not remove judicial review or statutory interpretation; it would just be conducted in another venue. The greatest risk would be the loss of integration and fragmentation of our apex courts (or divisions) in the various UK jurisdictions drifting away from one another or diminishing the speed and increasing the disorderliness of questions of constitutional importance being resolved.

The politics: why “possible” is not “probable”

It would devour the time of Parliament within an extended, highly technical bill, provoke consent battles with devolved governments, and incite intense debate as to the commitment of the UK to judicial independence. It will force the government to throw up a credible replacement that is visibly insulated from political pressure. Moving will be interpreted constitutionally as an attempt to redo the settlement post-2005, which had divorced the judiciary from the legislature, something Parliament itself championed two decades back. Even if legally defensible, the politics would be bruising.

What about simply clipping the Court’s wings?

Parliament could restrict the Supreme Court’s powers without abolishment; for example, limiting appeal routes or specifying what devolved questions may be referred. This would also require primary legislation and changes to numerous statutes. Politically, salami slicing may feel less dramatic than abolition but presents similar issues with coherence and, if the restrictions are aimed at politically sensitive cases, targeted as legislative retribution against the court, may, arguably, be incompatible with the spirit of the CRA’s independence duty.

A brief comparative perspective

There are few comparable democratic countries today that house their final court within the legislature; most have stand-alone apex courts or stand-alone constitutional courts. The 2009 reform to the House of Lords moved the UK’s final court out of the House of Lords and consolidated clarity of roles and optics with other jurisdictions and with the mainstream. To go back would be highly visible internationally and could attract an unfavorable comparison to the UK as a state with a reputation for upholding the rule of law; Parliament’s own account of the 2005 reform notes that it was about explicit separation.