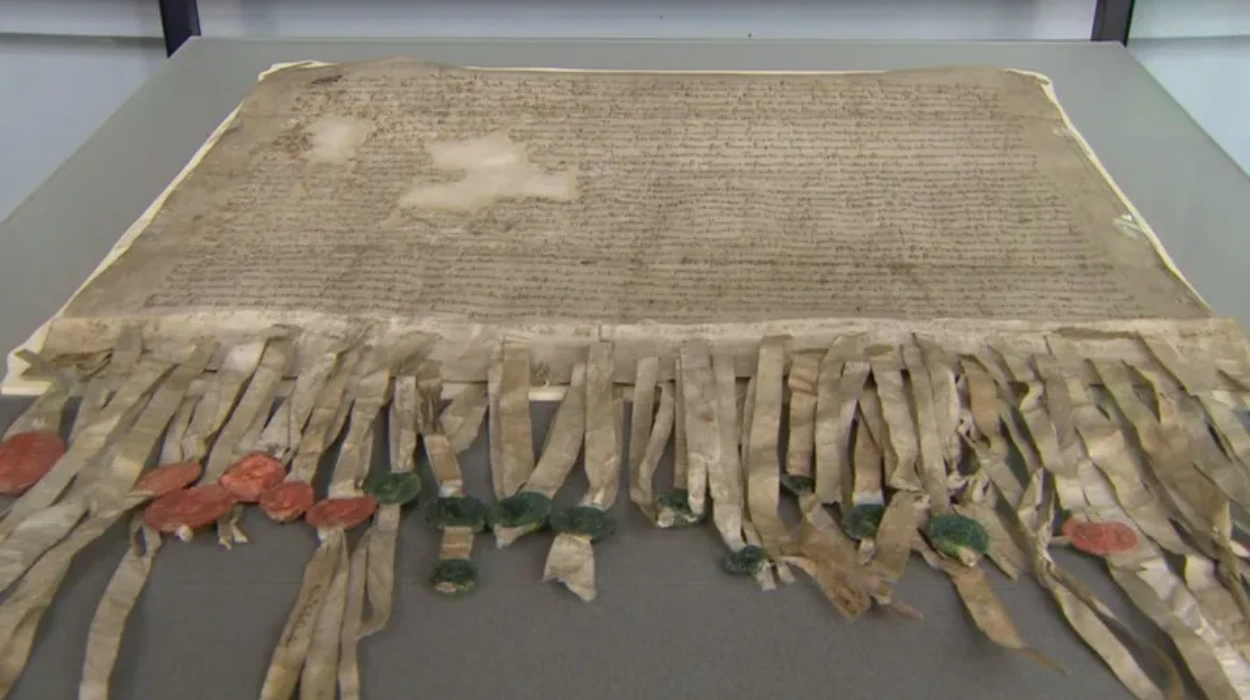

These are the best-known words in the Declaration of Arbroath, foremost among Scotland’s state papers and the most famous historical record held by the National Records of Scotland. The Declaration is a letter written in 1320 by the barons and the whole community of the kingdom of Scotland to the pope. It asks him to recognize Scotland’s independence and acknowledge Robert the Bruce as the country’s lawful king.

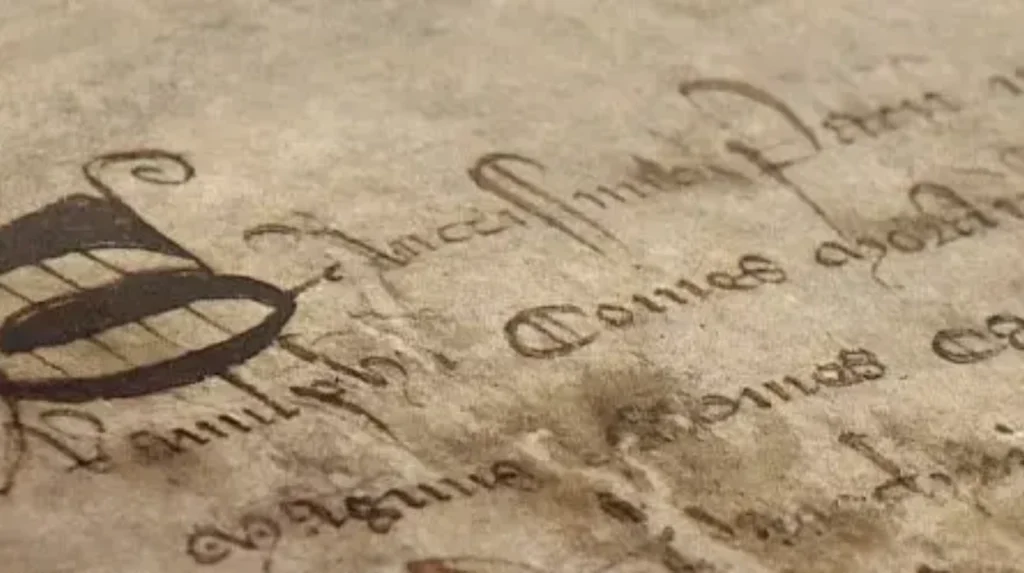

The Declaration was written in Latin and sealed by eight earls and about 40 barons. Over the centuries various copies and translations have been made, including a microscopic edition.

What was the Declaration of Arbroath?

It was not really a declaration and did not get that name until much later. It was a private missive to Pope John, which was endorsed by 39 of the most powerful Scottish barons and earls, who supported Bruce as king.

They were appealing for help to end the wars of independence with England, which had been going on for decades. Bruce had struck a blow to settle Scotland’s independence in 1314 at the Battle of Bannockburn, but there was no truce between the two nations, and the disputes raged.

Why write to the Pope?

The barons hoped the Pope, as the head of Western Christendom, could put pressure on King Edward II of England to achieve peace. It was also a subtle diplomatic attempt to get the Pope, who had clashed with Robert Bruce on a number of issues, to recognize him as the legitimate king of Scotland.

Pope John was no friend of King Robert, a man who had murdered a rival claimant to the throne in a church and had ignored papal decrees. In fact, the Pope was seeking to enforce his excommunication. The letter was an appeal from the nobles to lift the excommunication and recognize Robert I as the rightful king.

Cunning Diplomatic Letter or Constitutional Document?

There is considerable debate over the Declaration’s significance. It is simply a diplomatic document, while others see it as a radical movement in Western constitutional thought.

It could be viewed as a cunning diplomatic ploy by the Scottish barons to explain and justify why they were still fighting their neighbors when all Christian princes were supposed to be united in a crusade against the Muslims. All this, just at the point when they were about to retake Berwick, Scotland’s most prosperous medieval town. As an explanation, it failed to convince the pope to lift his sentence of excommunication on Scotland.

The Declaration of Arbroath: Scotland’s Voice for Freedom

Others analyze what the Declaration of Arbroath actually says. The Scottish clergy had produced not only one of the most eloquent expressions of nationhood but also the first expression of the idea of a contractual monarchy. Here is the critical passage in question:

‘Yet if he (Bruce) should give up what he has begun and agree to make us or our kingdom subject to the King of England or the English, we should exert ourselves at once to drive him out as our enemy and a subverter of his own rights and make some other man who was well able to defend us our king; for, as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule.

It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honors that we are fighting, but for freedom – for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.’

Modern Legacy of Arbroath

In 1998, former majority leader Trent Lott succeeded in instituting an annual “National Tartan Day” on 6 April by resolution of the United States Senate. US Senate Resolution 155 of 10 November 1997 states that “the Declaration of Arbroath, the Scottish Declaration of Independence, was signed on April 6, 1320, and the American Declaration of Independence was modeled on that inspirational document.” However, this claim is generally unsupported by historians.

In 2016 the Declaration of Arbroath was placed on the UK Memory of the World Register, part of UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme.

2020 was the 700th anniversary of the Declaration of Arbroath’s composition; an Arbroath 2020 festival was arranged but postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh planned to display the document to the public for the first time in fifteen years.

Were the barons aware of what the Declaration said?

There has been some debate about how much the nobles who sealed the document knew about what it said. Was the famous clause written only for the pope’s ears, or did they also have a domestic audience in mind? This is a key question in the debate about the Declaration’s significance.

If the barons named at the beginning were largely ignorant of its contents and were not expected to know what it said, then how could it have been written with an eye to the domestic political situation? How appropriate would it be to see it as a ‘declaration’ of constitutional significance if those who sealed it

thought it was simply a letter to the pope? The nobles could not have read and understood the Latin of the document. But they were also accustomed to dealing with this handicap. In this period almost all public documents were in Latin. A noble would normally have a clerk to read it and translate it for him before he sealed it.

Presumably on this occasion the nobles sent their clerks with their seals. It is hard to believe that the clerks would not have read the letter and reported back to their lords the main points of what it said. Those outside Robert I’s council may not have had a say in what the Declaration said, but the text could still have been written in the expectation that they would learn of its contents—especially the most dramatic parts.

Extract from the Declaration of Arbroath

The threat to drive Bruce out if he ever sold Scotland to English rule was a fantastic bluff. There was nobody else to take his place. The point is that the nobles and clergy are not basing their argument to the pope on the traditional notion of the Divine Rights of Kings. Bruce is king first and foremost because the nation chose him, not God, and the nation would just as easily choose another if they were betrayed by the king. The explanation also neatly covers the fact that Bruce had usurped John Balliol’s rightful kingship in the first place.

In spite of all possible motivations for its creation, the Declaration of Arbroath, under the extraordinary circumstances of the Wars of Independence, was a prototype of contractual kingship in Europe.