BELFAST (Parliament Politics Magazine) – Sinn Féin has called for a debate on a united Ireland, hailing its first victory in a Northern Ireland assembly election as a watershed moment for the British-controlled province.

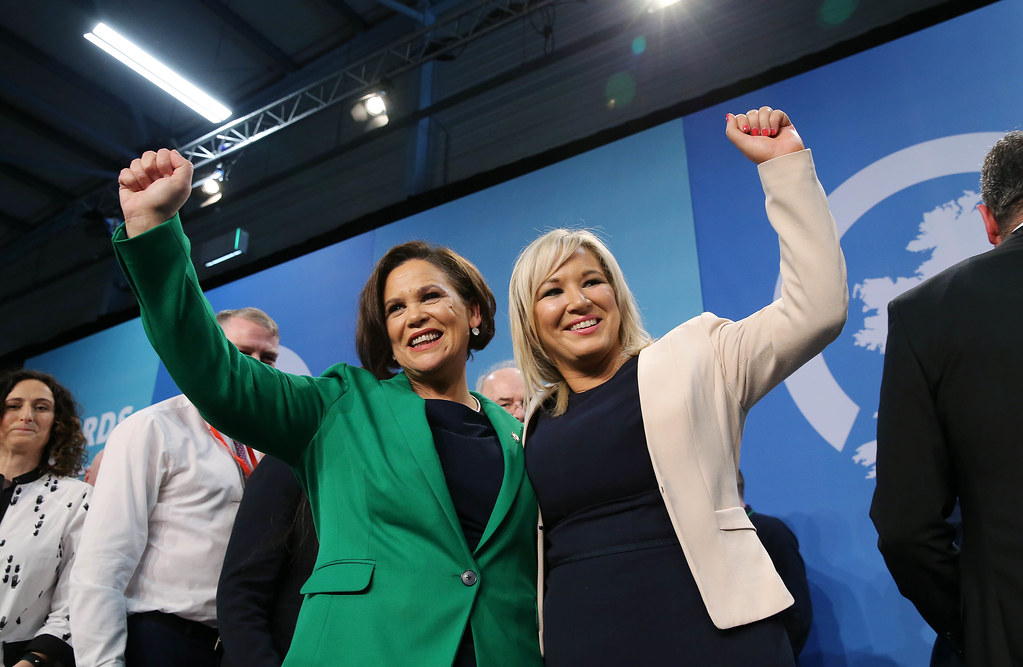

On Saturday, the party’s president, Mary Lou McDonald, sent a simple message to unions, saying, “Don’t be scared, the future is bright for us all.”

Unionists will have been worried by past assertions that they would want to see a border poll on Irish unification within five to ten years, but the party has intentionally played down its long-term ambition of a united Ireland.

Can Sinn Féin call a border election as Northern Ireland’s largest party?

No, categorically. Only the Northern Ireland secretary has that authority. Brandon Lewis flatly denied such a poll on Sunday, and his successors are unlikely to order a referendum with such far-reaching repercussions.

The Brexit result illustrated the dangers of referendums called without appropriate planning, as Sinn Féin’s deputy leader Michelle O’Neill brought to attention on the BBC’s leadership debate before the election.

The most recent such exercise in Ireland legalised abortion and is widely regarded as a model for contentious polls. It took years of planning, including citizen assemblies and draught laws approved in advance by parliament, so voters knew exactly what their decision would mean.

How can a border poll come about?

The Good Friday Agreement permits for a poll at some point, but does not specify the parameters, other than to say that the British government decides whether or not the Northern Ireland parties are allowed to participate.

If it appeared to him at any time that a majority of those voting would express a wish for Northern Ireland to stop being a member of the UK and become a part of a united Ireland, the Secretary of State shall make an Order in Council authorising a border poll.

Is the result of the election sufficient to constitute a majority in a poll?

Although the agreement does not specify what a majority is, experts suggest that a variety of metrics, not just an election outcome, would have to be used.

A group of academics led by Alan Renwick, deputy director of the constitution section at University College London, spent two years researching a possible border poll. Their 259-page report addresses all of the major concerns concerning how one might emerge and be designed.

They believe that majority support for a united Ireland would have to exist for some time, possibly between 51 and 55 percent, before the secretary of state would have to exercise their “mandated duty.”

Alan Whysall, another member of the UCL constitution unit, points out that a united Ireland was a long way off in 1998, and that the agreement’s text is hampered by severe gaps and uncertainties in the framework for a referendum.

Opinion polls, election results, qualitative research, a vote in Stormont, demographic data and seats won at elections are among the six sources of evidence suggested by UCL for a majority.

What is the significance of demographic data?

It is often assumed, correctly or incorrectly, that Catholics would support a united Ireland while Protestants would strive to maintain the status quo.

The most recent census data, which were released last summer, may suggest that Catholics have surpassed Protestants for the first time.

However, Peter Shirlow, head of the University of Liverpool’s Institute of Irish Studies, feels that as Northern Ireland’s peace solution matures, a new cohort may emerge. He refers to them as “secular unionists” from both spiritual backgrounds who want Northern Ireland to remain a part of the UK.