When you think of your family, in the country, it’s a heavy burden ”: in the north of France, where he tries to cross the Channel, Mohamed Yasir knows his mental health affected by his migratory journey. But for this Sudanese, the priority is to arrive in the United Kingdom.

Like many migrants, he left a country plagued by violence and put his life in danger in the hope of a better life. For now, he is camping in the copses on the outskirts of Calais, on the coast of northern France. In this city of 75,000 inhabitants, the supply of care, already insufficient for the locals, is almost inaccessible for foreigners passing through, who currently number around 800, according to Doctors Without Borders (MSF). The NGO therefore relaunched its operations there in the spring.

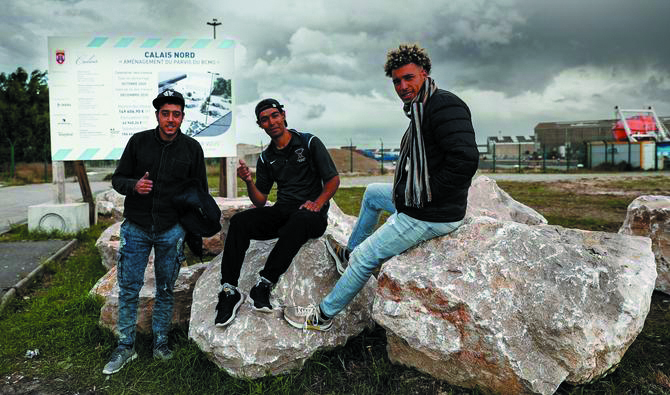

Every week, a psychologist, a nurse and intercultural mediators meet migrants in transit, on a vacant lot surrounded by several camps. Residents, mostly Sudanese, settle down for the time to charge their mobile phones. Around a table with a few games and hot coffee, tongues loosen.

Take care of me

Mohamed, 32, who left El Geneina in Darfur in early 2023 at the start of the war now ravaging Sudan, knows he will need psychological support. “When I found myself in the middle of the sea (Mediterranean Ed), on a small plastic boat, there was not enough gasoline, the captain was not trained, there were waves of two meters , there I regretted” to have left, he says. Rescued by an NGO at sea, he met a psychiatrist on board. “He told me to take care of myself before helping others (…) and gave me a paper with a diagnosis,” he says, without revealing its content.

For months, he has had no news of his wife and their two-year-old child, who lived with about fifteen relatives in the family home in Darfur. He can only hope that they were able to flee to Chad. “There I have to cross first”, to Great Britain, he says, hoping to resume studying architecture. But “when I arrive, as soon as I’m settled, I’ll start sessions,” he says. For those in transit, “I’m not going to scratch,” explains Chloé Hannebow, an MSF psychologist. “I will explain to them the mechanisms behind certain symptoms”, such as anxiety attacks, stomach aches or dark thoughts, and “give them some techniques to manage them”.

treated as objects

Many first complain of physical ailments and are seen by the nurse, Palmyre Kühl, before eventually being referred to the psychologist. In her tent that morning, Ms. Kühl examines a 30-year-old who arrived in May and complains of pain in his knees. “He had scars, I asked him what it was, and he started telling me he had been tortured” in Sudan, she says. “I offered to talk to someone about it, and he said yes right away.”

Among the most frequent pathologies observed: post-traumatic stress and depression. Since 2022, associations have identified at least three suicides of exiles on the coast. Others are losing ground, like this Sudanese recluse in a tent for months. His friends managed to cross and he remained alone, isolating himself more and more, says MSF, who went to meet him with a mobile team from the medico-psychological center in Calais.