Have you ever heard the phrase “the national debt” in the news and wondered what that actually means for Ireland? It is a number that comes up in conversation. It sounds scary, but we should try to understand what it means. How much is the Irish national debt, and more importantly, who actually owes the national debt? This article will guide you to break down this complicated concept into simple-to-understand words for you.

What is National Debt?

The Irish government collects money from us through taxes (income tax, VAT). But in most years, the government spends more than it collects (known as a budget deficit). So every year it has to borrow some money to cover this gap. The national debt is simply the total amount of money the Irish government has borrowed over the years and not yet paid back.

It is important to emphasize that the national debt is not the same as the national deficit. The national deficit is a shortfall in a single year, or in other words, how much more it has spent than it has collected, while the national debt refers to the pile of borrowed money that has accumulated from each of those yearly deficits.

How Big Is the Irish National Debt?

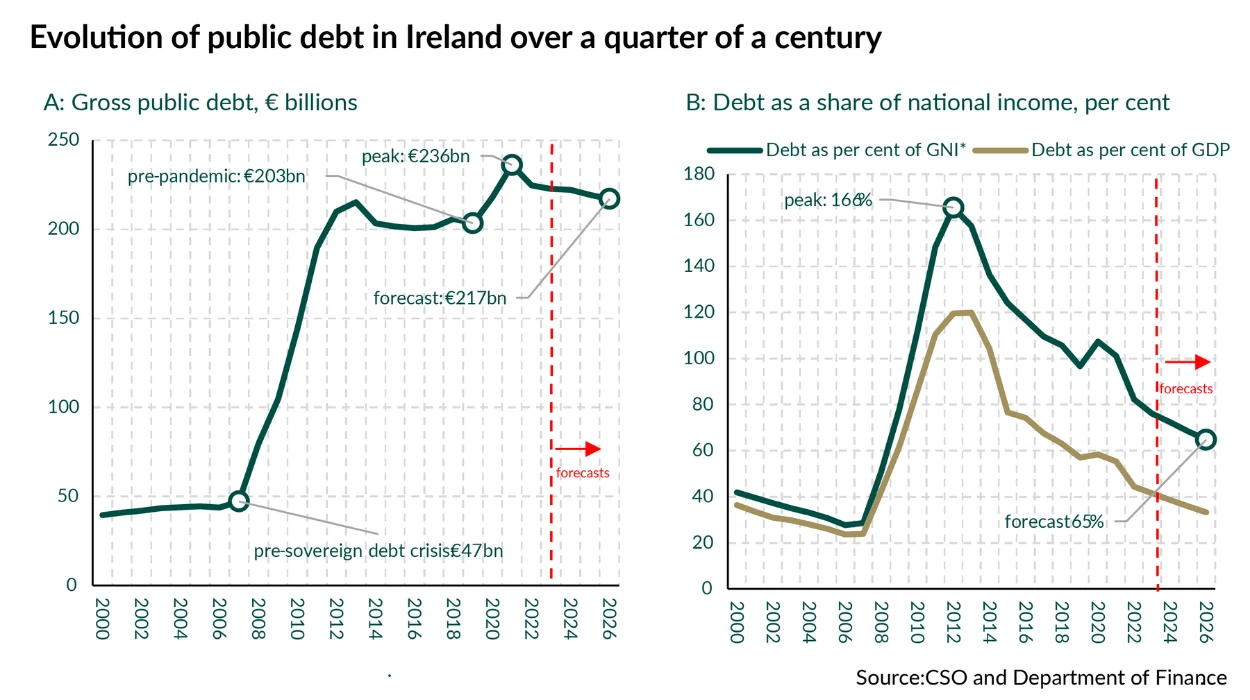

How large is the national debt of Ireland? The number is so large that it’s difficult to understand. As of 2024, Ireland’s general government debt stands at about €220 billion. That is €220,000,000,000. To put that massive number into perspective:

- Per Person: If one were to divide the debt equally amongst every man, woman, and child in Ireland, each person would owe approximately €42,000.

- Global Comparison: The national debt of Ireland is measured as a ratio to its economic strength (Gross Domestic Product, or GDP). This is called a “debt-to-GDP” ratio. Furthermore, Ireland’s debt is about 44% of its modified Gross National Income (GNI*), which is a more accurate measure of its economy. This number is high; it is lower than the EU average.

The bulk of the debt increased quickly during the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, when huge amounts were borrowed to bail out the banking system, fund health services, and pay for schemes such as the Pandemic Unemployment Payment to support the many people who lost their jobs.

Who Does Ireland Owe This Money To?

This is the most crucial part of the question. The Irish government doesn’t borrow from a single bank; it borrows by selling government bonds.

What is a government bond?

A bond is essentially an IOU. The government sells an IOU to investors, and the government is saying, “Lend us €100 today, and we’ll pay you back in 10 years and pay you a little interest each year.

Who owns these bonds?

A big long list of investors from all over the world owe the money:

- Investment Funds and Pension Funds: This is the largest group. It consists of investment funds and the pension funds that manage the retirement savings for people in Ireland and abroad. They buy Irish bonds because they are a relatively safe way to invest very large sums of money.

- Other Countries and International Bodies: The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and other European institutions gave loans to Ireland during the government financial crisis.

- Banks and Insurance Companies: Both Irish banks and international banks hold Irish government bonds in their investment portfolios.

- Individual Investors: Normal people can buy government bonds too; it isn’t as common. In short, the national debt is owed to a global group of investors because they have lent the money to Ireland because they think Ireland is good for it and will pay it back.

Is the Debt Getting Better or Worse?

The good news is that Ireland’s debt situation is better today than it was at the height of the last crisis. The Irish economy is much bigger today. Because the economy is bigger, the debt has shrunk, reflected in the fact that debt as a percentage of GNP is lower. Since the economic crisis, the government has also been careful to deliver a budget surplus (where the government takes in more money than it spends), which allows it to start reducing the national debt rather than increasing it.

Emerging challenges, including housing, climate change, and an aging population, are requiring significant public and private investment. The government must balance its need for investment in projects that will help Ireland meet these future challenges and also manage its national debt.

How Does the National Debt Affect Me?

You may hope a figure this large won’t affect your everyday life, but it does in a number of ways.

- Interest Payments: Governments must pay interest on their huge debt. In 2024, the interest on the national debt is expected to be approximately €4.7 billion. This is a huge amount of money to build thousands of new homes or employ tens of thousands of nurses and teachers. Again, this is money that is not available to improve public services, cut taxes, or invest in infrastructure.

- Economic Flexibility: The level of debt means the government has less flexibility in a new crisis. If another pandemic or recession hits, they may find it impossible to borrow more to protect people without also worrying lenders could panic and stop further lending to a country with big debts.

- Taxes and Services: Ultimately, high debt means hard choices about the future. To manage the debt, a government might feel they have to raise taxes or cut services (healthcare and education) to free money to pay the interest payments.

A National Mortgage for Our Future

So, how big is the Irish national debt? It is undoubtedly enormous, an extraordinary €220 billion collection of past IOUs accumulated over crises. And who owes it? We do national debt, not personal debt. A responsibility not as individuals.

The national debt can be understood without the panic it galvanizes. The national debt is an awareness, like a national mortgage. It got us through some tough times, but we need to keep up with the mortgage payments. Interest on the mortgage restricts what we can do as a nation today.

The necessary conversation must address how we approach this national responsibility. How do we balance our approach to paying it down and investing for a better, fairer future for everyone in Ireland? This is one of the most important conversations we can have about our nation’s future.